Ransomed — Malware Analysis Walkthrough

Dynamic analysis and memory forensics: stack-strings, API resolution, shellcode and process hollowing.

Overview

| Platform | CyberDefenders |

| Category | Malware Analysis |

| Difficulty | Hard |

| Focus | Dynamic Analysis · Process Hollowing · String Obfuscation · API Resolution |

| Lab Link | Ransomed |

The Ransomed challenge is a malware analysis lab that simulates a real-world incident where suspicious memory activity is detected on a workstation. Initial telemetry points to an unknown executable exhibiting high entropy, a common indicator of packing or obfuscation.

At first glance, the binary does not immediately reveal its intent through static inspection alone. Instead, its true behavior unfolds only at runtime — where memory allocation, shellcode execution, and process manipulation become visible.

This challenge is not about signature matching or quick wins. It is about reconstructing execution flow, understanding why specific Windows APIs are used, and recognizing how common malware techniques appear in practice.

Objective

The goal of this analysis is to reconstruct the malware’s execution chain using a combination of:

- Static analysis (PE structure, entropy, sections)

- Dynamic analysis (debugging, API tracing)

- Behavioral reasoning (what each action enables next)

By the end of the investigation, we aim to clearly answer:

- How the malware unpacks itself

- How it hides strings and resolves APIs dynamically

- How it executes shellcode

- How it injects a payload into another process

- What specific process injection technique is used

Tools Used

Throughout this analysis, the following tools are used:

- PE inspection tools (entropy, sections, headers)

- Disassembler (static code inspection)

- x32 debugger (runtime behavior, API tracing)

- Shellcode debugger/emulator (when needed)

Q1 — Entropy Analysis & Initial Triage

Question

What is the value of entropy?

How entropy works

Entropy measures randomness of bytes:

- Low entropy (~3–5): readable data, strings, code

- High entropy (~7+): encrypted / packed / compressed

Windows executables that are clean and unpacked rarely sit close to 8.

So when entropy is high, static analysis alone will lie to you.

What we do here

We inspect the binary using a PE analysis tool (PEStudio / DIE / similar) and check:

- Overall file entropy

- Whether entropy is uniform or concentrated

- Whether it aligns with later behavior (unpacking, shellcode, etc.)

This tells us how much trust to put in static findings.

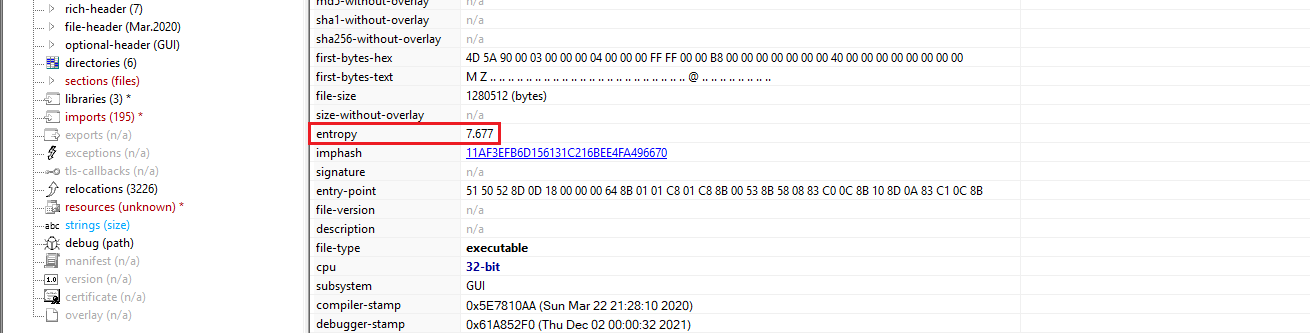

The First Page of the PEStudio show us :

PEStudio showing entropy value of 7.677

PEStudio showing entropy value of 7.677

The entropy value observed is:

1

7.677

An entropy value of 7.677 is very high and strongly suggests:

- The binary is packed or obfuscated

- Payload is likely unpacked at runtime

- Static strings and imports will be incomplete or misleading

This immediately justifies:

- Debugging

- Memory analysis

- Runtime API tracing

At this point, any analyst who continues purely statically is already behind.

Q2 — Section Analysis

Question

What is the number of sections?

What we look for

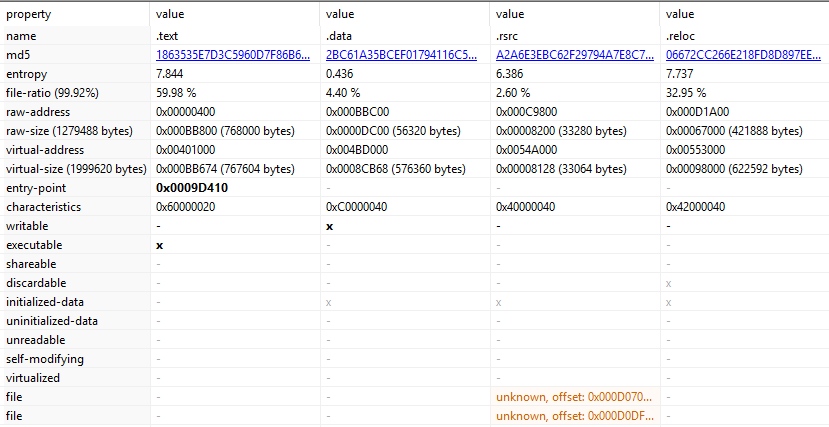

From the same utility we used firt, PEStudio we’ll select the section tab and we’ll see :

Four sections: .text, .data, .rsrc, .reloc

Four sections: .text, .data, .rsrc, .reloc

we noticed four sections : .text, .data, .rsrc, .reloc so the binary contains:

1

4 sections

So here’s the key insight:

The malware does not rely on exotic sections to hide. It relies on runtime behavior.

This aligns perfectly with what entropy already told us:

- Code and payload are likely unpacked dynamically

- Strings and APIs may not exist in plaintext on disk

This is an important lesson for readers:

- Normal structure ≠ benign behavior

Q3 — String Obfuscation Technique

Question

What is the name of the technique used to obfuscate string?

At this stage we know:

- Entropy is high → something is hidden

- Sections look normal → hiding is logical, not structural

So the next question is:

Where are the strings?

And the answer is:

- Not in

.rdata - Not visible via static string extraction

- Constructed at runtime

This immediately narrows it down to:

- Stack strings

- Heap strings

- Decryption routines

So we open IDA.

What we look for in IDA

In IDA, stack strings look like this:

- No readable string in

.rdata Instead:

- Multiple

mov,push,xor,add - Writing single bytes / dwords

- To

[esp+X]or[ebp-X]

- Multiple

Then passing a pointer to:

GetProcAddressLoadLibraryA- or another API

The string never exists as a contiguous string in the binary.

Look at this part from IDA (exactly +0x9bee0) :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

// Sets up memory protection - gets VirtualProtect address and marks decrypted memory region as executable (PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE).

int setup_virtual_protect()

{

_BYTE v1[4]; // [esp+4h] [ebp-4h] BYREF

strcpy(g_api_name_buffer, "kernel32.dll");

g_kernel32_handle = (int)GetModuleHandleA(g_api_name_buffer);

strcpy(g_api_name_buffer, "VirtualProtect");

g_VirtualProtect_addr = (int)GetProcAddress((HMODULE)g_kernel32_handle, g_api_name_buffer);

return ((int (__stdcall *)(int, SIZE_T, int, _BYTE *))g_VirtualProtect_addr)(

g_decrypted_code_ptr,

g_junk_condition,

64,

v1);

- Strings are not stored in plaintext in the binary

- They are built byte-by-byte or dword-by-dword

- Construction happens on the stack

- The buffer is used immediately and often wiped later

- This defeats:

strings.exe- static YARA rules

- naive reverse engineering This is a classic malware evasion technique.

This technique is known as stack strings.

By constructing strings dynamically on the stack, the malware effectively evades static string analysis tools and signature-based detection. This behavior is commonly observed in real-world malware and aligns with the high entropy observed earlier.

Q4 — Memory Allocation for Shellcode

Question

What is the API that used malware-allocated memory to write shellcode?

At this point in the analysis, we already know:

- The malware hides strings using stack strings

- APIs are resolved dynamically

- Static analysis alone is unreliable

So the next logical question is:

Where does the decrypted or unpacked payload live in memory?

Malware that unpacks itself must allocate memory to:

- Store decrypted code

- Change permissions

- Transfer execution

So we are now looking for memory allocation APIs.

What we look for in IDA

Inside IDA, we search for:

- Calls to memory management APIs

Especially APIs related to:

- Allocation

- Protection changes

- Execution

Typical candidates include:

VirtualAllocVirtualAllocExHeapAllocNtAllocateVirtualMemory

Because APIs are resolved dynamically, we don’t rely on imports. Instead, we follow GetProcAddress usage and observe how the returned function pointers are used.

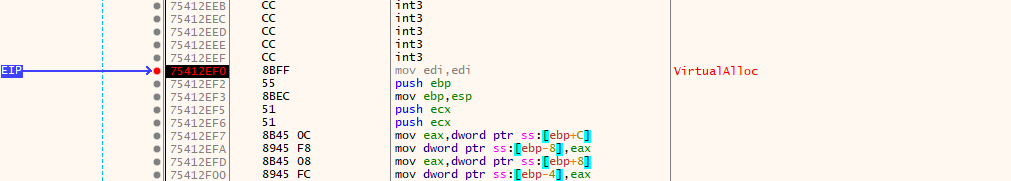

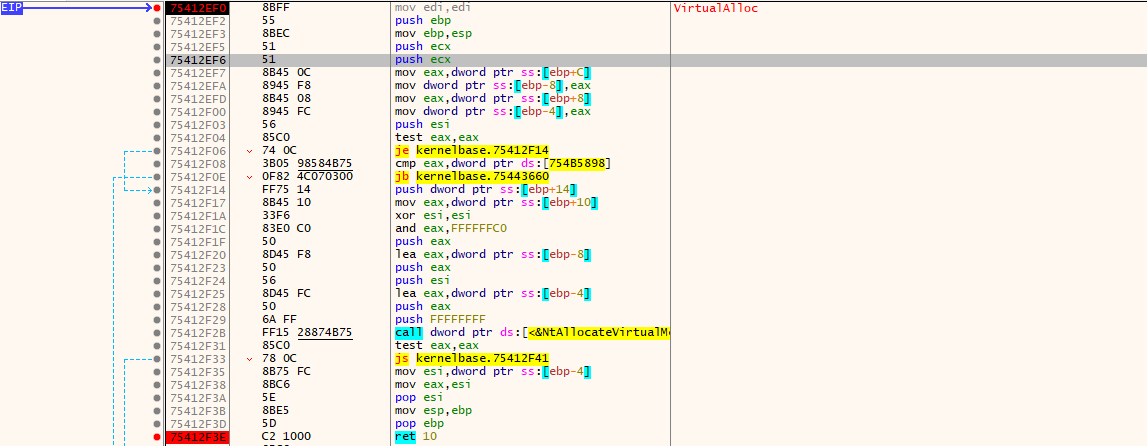

Evidence from the code

From the earlier analysis, we already identified dynamic resolution of VirtualProtect. Tracing backward and forward in the code reveals that memory is allocated prior to execution and decryption routines. we can demostrate that by just setting a breakpoint at the VirtualAlloc Call in the debugger.

Breakpoint set at VirtualAlloc in x32dbg

Breakpoint set at VirtualAlloc in x32dbg

The API used by the malware to allocate memory for writing shellcode is:

1

VirtualAlloc

This API is used to reserve and commit memory regions that later hold decrypted shellcode.

This is a prerequisite for:

- Shellcode execution

- Process injection

- Unpacking routines

At this stage, allocation alone does not prove injection — but it confirms that runtime code generation/execution is happening.

This finding fits naturally into the execution chain we are reconstructing and prepares us for the next critical step: memory permissions.

Q5 — Memory Protection of Allocated Region

Question

What is the protection of allocated memory?

Allocating memory alone is not enough to execute shellcode.

For code to run, the memory must be:

- Executable

- And usually Writable during decryption/unpacking

So after identifying VirtualAlloc, the next question is obvious:

What permissions does the malware assign to that memory?

This tells us:

- Whether the memory is intended for code execution

- Whether the malware follows a decrypt-then-execute pattern

What we look for

In IDA, we inspect:

- The arguments passed to the resolved allocation/protection API

- Especially the protection constant

Typical values to watch for:

| Value | Meaning |

|---|---|

0x04 | PAGE_READWRITE |

0x20 | PAGE_EXECUTE_READ |

0x40 | PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE |

Malware very often uses 0x40 because it allows:

- Writing decrypted payload

- Executing it immediately afterward

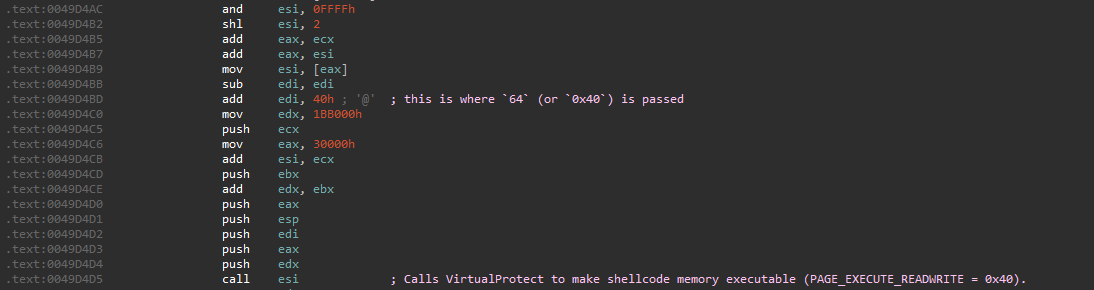

Evidence from the code

From the previously identified routine:

1

2

3

4

5

6

((void (__stdcall *)(char *, int, int, _DWORD *))(v10 + v11))(

ImageBaseAddress + 1814528,

196608,

64,

v14

);

The third argument passed is:

1

64

In hexadecimal:

1

0x40

Which corresponds to:

1

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE

Value 0x40 (PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE) passed as protection

Value 0x40 (PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE) passed as protection

The protection of the allocated memory is:

1

ERW (PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE)

This confirms that the allocated region is intended to store and execute shellcode, not just data.

Q6 — Transfer of Execution to Shellcode

Question

What assembly instruction is used to transfer execution to the shellcode?

From previous questions, we already know:

VirtualAllocis used to allocate memory- The memory protection is PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE

- Shellcode is written into that region

But allocation is not execution.

So the correct next step is:

Trace execution immediately after

VirtualAllocreturns and observe how the allocated address is used.

This requires a debugger.

Dynamic Analysis Setup

At runtime, we set a breakpoint on:

1

kernel32!VirtualAlloc

Breakpoint hit at VirtualAlloc

Breakpoint hit at VirtualAlloc

Once the breakpoint hits:

- Step out of

VirtualAlloc - Observe the return value

- Follow how the program uses that pointer

btw the return value of VirtualAlloc is critical — it is the base address of the shellcode.

What happens after VirtualAlloc returns

After stepping a few instructions, we observe the following workflow:

- The return value of

VirtualAllocis saved on the stack (typically into a local variable[ebp-4]) The malware performs additional setup:

- Writes/decrypts data into the allocated memory

- Prepares execution context

- Execution is indirectly transferred to the allocated region

This confirms that the allocated memory is an executable payload.

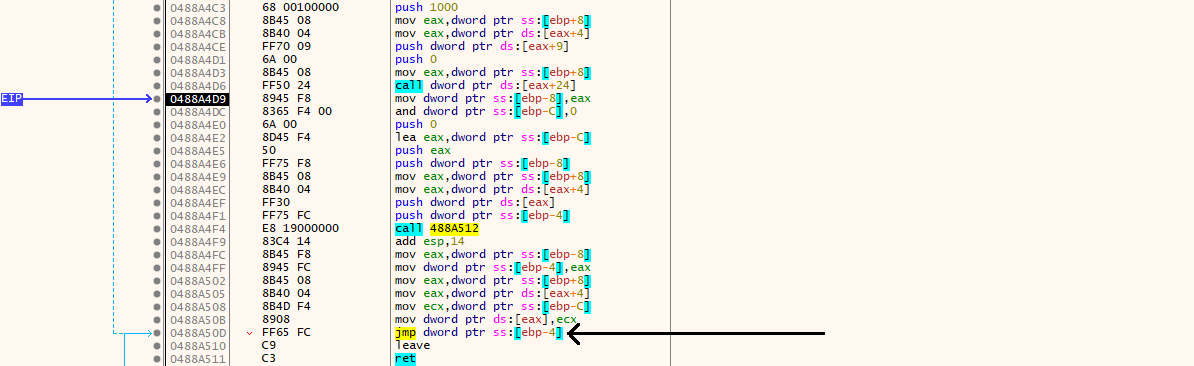

After tracing execution, the final control transfer is done via:

1

jmp dword ptr ss:[ebp-4]

Indirect jump transferring execution to shellcode

Indirect jump transferring execution to shellcode

This instruction:

- Reads the address returned by

VirtualAlloc - Redirects execution to that memory region

- Hands control directly to the shellcode

There is no function call, no symbol, and no import involved.

Note that by using an indirect jump via the stack:

- Avoids direct calls to suspicious addresses

- Makes static control-flow analysis harder

- Cleanly separates loader code from payload code

The assembly instruction used to transfer execution to the shellcode is:

1

jmp dword ptr ss:[ebp-4]

Q7 — Dynamic API Resolution (kernel32)

Question

What is the number of functions the malware resolves from kernel32?

From the previous questions, we already proved:

- Shellcode is allocated with

VirtualAlloc - Memory is executable

- Execution jumps into the payload

At this point, IDA is no longer enough.

To answer this cleanly and reliably, we extract the payload and analyze it independently.

Locate the payload in memory

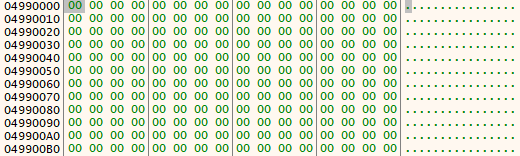

We break on the return of VirtualAlloc:

1

75412F3E | C2 1000 | ret 10

After the return:

EAXcontains the base address of the allocated memory

Observed value:

1

EAX = 0x04990000

At this moment, the memory is empty — expected, since the payload has not been copied yet.

Memory at allocated address is empty before payload copy

Memory at allocated address is empty before payload copy

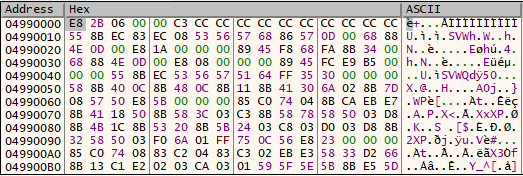

After stepping forward a few instructions, the payload is written into that region.

Payload written to allocated memory region

Payload written to allocated memory region

- Payload confirmed at address

0x04990000.

Dump the payload from memory

The allocation size passed to VirtualAlloc is:

1

0x0011B000

We dump the payload using x32dbg:

1

savedata payload.bin, 04990000, 0011B000

Now we have the raw shellcode payload extracted from memory.

Analyze the payload with scdbg

We load the dumped payload into scdbg and search for resolved APIs:

1

scdbg.exe /f payload.bin /findsc

scdbg identifies the shellcode entry point and begins emulation. After selecting the correct entry index, the resolved APIs are displayed.

Identify kernel32-resolved functions

From the scdbg output, the payload resolves APIs from multiple modules:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

4017fa LoadLibraryA(kernel32)

401831 GetProcAddress(WinExec)

40189f GetProcAddress(CreateFileA)

4018de GetProcAddress(WriteFile)

40194c GetProcAddress(CloseHandle)

4019cf GetProcAddress(CreateProcessA)

401a60 GetProcAddress(GetThreadContext)

401ad5 GetProcAddress(VirtualAlloc)

401b58 GetProcAddress(VirtualAllocEx)

401bc6 GetProcAddress(VirtualFree)

401c5e GetProcAddress(ReadProcessMemory)

401cfd GetProcAddress(WriteProcessMemory)

401d8e GetProcAddress(SetThreadContext)

401e03 GetProcAddress(ResumeThread)

401ea9 GetProcAddress(WaitForSingleObject)

401f0c GetProcAddress(GetModuleFileNameA)

401f96 GetProcAddress(GetCommandLineA)

We focus only on APIs resolved via kernel32. Counting the GetProcAddress calls targeting kernel32. The malware dynamically resolves:

1

16 functions from kernel32.dll

Q8 — Strings Obfuscated After RegisterClassExA

Question

The malware obfuscates two strings after calling RegisterClassExA. What is the first string?

Runtime setup

At this stage, static analysis is useless for strings.

We know that RegisterClassExA forces plaintext strings, so the correct move is:

Set a breakpoint on:

1

user32!RegisterClassExA

- Let execution stop at the function entry

- Inspect the stack arguments before the call executes

At the breakpoint, execution stops at:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

755779F0 | 8BFF | mov edi,edi |

755779F2 | 55 | push ebp |

755779F3 | 8BEC | mov ebp,esp |

755779F5 | 8B4D 08 | mov ecx,dword ptr ss:[ebp+8] |

755779F8 | 8339 30 | cmp dword ptr ds:[ecx],30 |

755779FB | 0F85 0E260500 | jne user32.755CA00F |

75577A01 | 6A 01 | push 1 |

75577A03 | 68 80000000 | push 80 |

75577A08 | 6A 00 | push 0 |

75577A0A | 33D2 | xor edx,edx |

75577A0C | E8 BC100400 | call user32.755B8ACD |

75577A11 | 5D | pop ebp |

75577A12 | C2 0400 | ret 4 |

This confirms we are inside RegisterClassExA, before any processing happens.

Inspecting the stack

At the breakpoint, the stack layout is:

1

2

3

4

5

[esp+4] = 007EB85C

[esp+8] = 646F6173

[esp+0C] = 6F6E666B

[esp+10] = 75396173

[esp+14] = 00006E69

Interpreting these DWORDs as ASCII (little-endian):

1

73 61 6F 64 6B 66 6E 6F 73 61 39 75 69 6E

Which decodes to:

1

saodkfnosa9uin

Following the pointer confirms the same string in memory:

Stack revealing the obfuscated string at runtime

Stack revealing the obfuscated string at runtime

After RegisterClassExA returns:

- This memory region is modified

- The string is overwritten / obfuscated

- The plaintext string no longer exists in memory

This confirms:

- Runtime string decryption

- API-forced exposure

- Immediate cleanup to evade memory inspection

The first string that is revealed and then obfuscated after calling RegisterClassExA is:

1

saodkfnosa9uin

This string exists only briefly at runtime, which is exactly why breaking on the API is the correct approach.

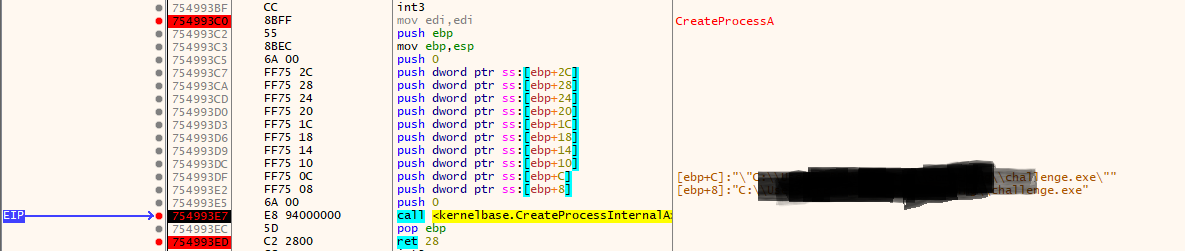

Q9 — CreateProcessA & dwCreationFlags

Question

What is the value of dwCreationFlags of CreateProcessA?

Runtime breakpoint

At this stage, the malware is about to spawn a new process. We set a breakpoint on:

1

kernel32!CreateProcessA

Execution stops inside the API wrapper, right before the call is forwarded to CreateProcessInternalA:

1

754993E7 | call kernelbase.CreateProcessInternalA

Breakpoint hit inside CreateProcessA

Breakpoint hit inside CreateProcessA

Register state at breakpoint

At the moment of the call, the registers are:

1

2

3

4

EIP : 754993E7 kernelbase.CreateProcessInternalA

EBP : 007EB77C

ESP : 007EB74C

EDX : "C:\Users\XXX\challenge.exe"

This confirms:

- We are inside

CreateProcessA - Arguments are already set up

- The stack frame is stable

At this point, arguments must be read via EBP, not ESP.

Locating dwCreationFlags

On x86, the argument layout for CreateProcessA inside the function is:

1

2

3

4

5

6

[EBP+08] lpApplicationName

[EBP+0C] lpCommandLine

[EBP+10] lpProcessAttributes

[EBP+14] lpThreadAttributes

[EBP+18] bInheritHandles

[EBP+1C] dwCreationFlags ← target

Using EBP = 0x007EB77C, we dump memory around the stack frame.

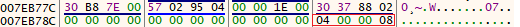

Memory dump:

1

007EB78C 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 04 00 00 08

The bytes at offset EBP+1C are:

1

04 00 00 08

Stack dump showing dwCreationFlags value at [EBP+1C]

Stack dump showing dwCreationFlags value at [EBP+1C]

Decoding the value

Interpreting the value as little-endian:

1

0x08000004

Breaking it down:

1

2

0x00000004 → CREATE_SUSPENDED

0x08000000 → CREATE_NO_WINDOW

The value of dwCreationFlags used by the malware is:

1

0x08000004

This confirms that the newly created process is intentionally paused so that its memory can be manipulated before execution resumes.

Q10 — Process Injection Technique

Question

The malware uses a process injection technique. What is its name?

Based on the execution flow observed throughout the analysis:

- A new process is created in a suspended state (

CREATE_SUSPENDED) - The original process image is unmapped

- Memory is allocated in the target process

- A payload is written into the target process memory

- The thread context is modified

- Execution is resumed

This sequence of actions corresponds to the following injection technique:

1

Process Hollowing

No further demonstration is required, as each step of this technique has already been confirmed in the previous questions.

Q11 — Payload Injection API

Question

What is the API used to write the payload into the target process?

Execution flow

After the malware finishes its initial setup and returns from RegisterClassExA, execution continues through a short sequence of Windows APIs that clearly indicate process injection activity.

The observed call flow is:

1

2

3

4

5

6

ReadProcessMemory

GetThreadContext

NtUnmapViewOfSection

VirtualAllocEx

NtWriteVirtualMemory

WriteProcessMemory

This sequence shows the malware preparing a remote process, allocating memory inside it, and then writing the payload.

Final write operation

Although both native (Nt*) and user-mode APIs appear in the chain, the actual user-mode API responsible for writing the payload into the target process is:

1

WriteProcessMemory

This is the definitive API that copies the malicious payload into the remote process address space.

This confirms the final stage of the process hollowing technique and completes the malware execution chain.

Conclusion

The Ransomed sample illustrates a classic multi-stage loader used in real malware: packed on disk, builds essential strings at runtime, allocates executable memory, executes shellcode, and compromises another process using process hollowing. By stepping through its behavior with x32dbg and validating observed API calls with scdbg, we reconstructed the full execution chain with confidence.